Author Information

N’guessan N’guessan Olivier (Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé, Laboratoire de Biodiversité et d’Ecologie Tropicale,Boîte Postale, Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire)

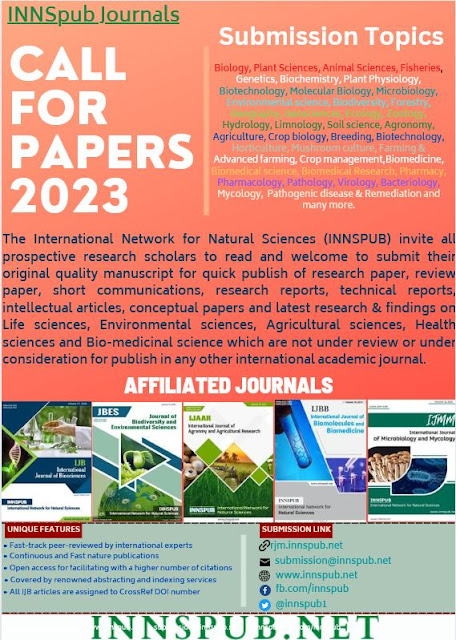

Journal Name

Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences | JBES

Publisher Name

International Network For Natural Sciences | INNSpub

Abstract

Nine

hundred juveniles of Archachatina marginata aged about two weeks, with an

average live weight of 2.25 g with an average shell length of 20.12mm were

monitored in culture for six (6) months on five types of substrates [S1 (soil

collected in a cassava plantation: Manihot sp.), S2 (S1 with 10% oyster shell

meal), S3 (S1 with 10% sawdust), S4 (S1 with 5% oyster shell meal and 5%

sawdust) and S5 (uncultivated forest soil). Four diets including two industrial

(D1 and D 2 of 12% and 16% calcium respectively) and two based on fodder (D3

and D4 based on leaves and fruit of the papaya (Carica papaya) on the one hand

and a mixture of papaya leaves and taro (Xanthosoma maffafa) on the other hand,

were used. In order to determine the best combinations inducing the best growth

performance, 20 combinations were formed at the rate of 45 spat for each

combination; three replicas of 15 spat each. This study showed that the

combination of diet and livestock substrate influences the growth of Archachatina

marginata. Although the best feed is D1 (74.68 g and 7.94cm) and the best

substrate is S2 (77.12 g and 7.79cm), the best combinations are D2S3 (69.37 g

and 7.47cm), D1S4 (74.68 g and 7.94cm and D4S2 (77.12 g and 7.79cm). The

combined effect of the high level of dietary calcium and that of the culture

substrate does not promote good growth of snails. This work will help improve

the production of African giant snails and provide important data for anyone

wishing to engage in the breeding of these animals.

Introduction

Naturally available food resources play a fairly substantial role in populations (Sodjinou et al., 2002). Among these resources, African giant snails (or Achatines) belonging to the family Achatinidae are found there. These snails are highly valued by many African populations (Zongo 1995). For example, Achatine meat is the most consumed meat in South Benin ahead of aulacode, chicken, sheep or goats, beef and pork (Sodjinou et al., 2002). It is estimated that in Côte d'Ivoire, the population eats 7.9 million kg of snails per year, while in Ghana; demand clearly exceeds production capacity (Cobbinah et al., 2008).

Unfortunately, these protein resources are becoming scarce in their natural environment. To compensate for these deficits, heliculture is one of the alternatives to diversify the sources of animal protein of populations. It is therefore right that initiatives to breed these animals should be carried out in order to satisfy the ever-increasing demand for their consumption, but also to ensure the sustainability of the resource. Thus, several research initiatives on the pace of activity, growth (Ejidike et al., Otchoumou et al., 2004; Kouassi et al., 2016), on reproduction (Otchoumou et al., 2005, Kouassi, 2008) as well as on snail farming substrate were supported (Kouassi et al., 2016; Awohouedji et al., 2017). Indeed, the success of such breeding goes beyond the control of the feed, the breeding substrate, the pathology of these animals, but also and above all by a healthy appreciation of the food according to the different types of breeding substrate.

Thus,

the substrate is a key element for snails as it is both a source of mineral

nutrients and a refuge. In terms of snail production, several studies have

shown the effect of feeding (Kouassi et al., 2007, Kouassi, 2002) or farming

substrate on the growth and reproduction of these animals by a variation in

calcium levels. However, to our knowledge, no studies have yet been devoted to

the combined effect of diet and substrate. The objective of this study is to

highlight the combined effect of diet and culture substrate on the live weight

and growth of the shell of Archachatina marginata in order to optimize its

rearing. It was therefore necessary to evaluate the combined effect of food and

substrate on the weight and shell growth of snails. Check out more by following the link Interaction on the diet and substrate on the growth of Archachatina marginata in breeding

Reference

Awohouedji

DYG, Attakpa EY, Babatounde S, Alkoiret TI, Ategbo JM, Aman JB, Kouassi KD,

Karamoko M, Otchoumou A. 2011. Effet de la teneur en poudre de coquille

d’huître dans le substrat d’élevage sur la croissance d’Archachatina marginata,

Journal of Applied of Biosciences 47, 3205-3213.

Bouye

TR, Ocho-Anin AAL, Memel JD, Otchoumou A. 2017. Effet de l’amendemant au

carbonate de calcium (mikhart) de substrat d’élevage sur les performances de

reproduction de l’escargot Achatina achatina (Linné 1758).

Chevalier

H. 1992. L’élevage des escargots: production et préparation du petit gris,

Edition du point vétérinaire, Paris 144 p.

Cobbinah

JC, Adri V, Ben O. 2008. L’élevage d’escargots : Production, transformation et

commercialisation. Première édition, Wageningen, (Pays-Bas) 84p.

Ebenso

I. E. 2003. Dietary calcium supplements for edible tropical land snails Archachatina

marginata in Niger Delta, Nigeria. Livestock Research for Rural Development 15(5).

Ejidike

BN, Afolayant TA, Alokan JA. 2004. Observations on some climatic variables and

dietary influence on the performance of cultivated African giant land snail (Archachatina

marginata): notes and records. Pakistan journal of Nutrition 3(6), 362-364.

Graham

SM. 1978. Seasonal influences on the nutritional status and iron consumption of

a village people in Ghana. University of Guelph. Canada (Thesis) 180p.

Jess

S, Mark RJ. 1989. The interaction of the diet and substrate on the growth of Helix

aspersa (Müller) var. maxima. Slug Snails Word Agriculture 41, 311-317.

Kouassi

KD, Aman JB, Karamoko M. 2016. Growth performance of Archachatina marginata

bred on the substrate amended with industrial calcium: Mikhart. International

Journal of Science and Research 5(1), 582-586.

Kouassi

KD, Aman JB. 2014. Effet de l’amendement du substrat d’élevage en différentes

sources de calcium sur la croissance de Archachatina marginata. Journal of

Advances in Biology 6(1), 835-842.

Kouassi

KD, Otchoumou A, Dosso H. 2007. Effets de l’alimentation sur les performances

biologiques chez l’escargot géant Africain: Archachatina ventricosa (Gould

1850) En Élevage Hors sol. LRRD 19, 1620.

Kouassi

KD. 2002. Impact de trois espèces d’escargots sur quelques plantes de

l’université d’Abobo-Adjamé: Inventaire et préférence alimentaire. Mémoire de

DEA, UFR-SN, Université d’Abobo-Adjamé/Abidjan – Côte d’Ivoire 48p.

Kouassi

kD. 2008. Effet de l’alimentation et du substrat d’élevage sur les performances

biologiques de Archachatina ventricosa (Gould 1850) et quelques aspects de la

collecte des escargots géants de Côte d’Ivoire. Thèse unique, Université

d’Abobo-Adjamé; n°32, 125p.

Otchoumou

A, Dosso H, Fantodji A. 2003. Elevage comparatif d’escargots juvéniles Achatina

achatina (Linné, 1758); Achatina fulica (Bowdich, 1820) et Archachatina

ventricosa (Gould, 1850): effets de la densité animale sur la croissance,

l’ingestion alimentaire et le taux de mortalité cumulée, Revue Africaine de

Santé et de Production Animale 1(2), 146-151.

Otchoumou

A, Dupont-Nivet M, Dosso H. 2004. Les escargots comestibles de Côte d’Ivoire:

effets de quelques plantes, d’aliments concentrés et de la teneur en calcium

alimentaire sur la croissance d’Archachatina ventricosa (Gould, 1850) en

élevage hors-sol en bâtiment. Tropicultura 22(3), 127-133.

Otchoumou

A, Dupont-Nivet M, N’da K, Dosso H. 2005. L’élevage des escargots comestibles

africain: effet de la qualité du régime et du taux de calcium alimentaire sur

les performances de reproduction d’Achatina fulica (Bowdich, 1820). Livestock

Research for Rural Development. 17(10) www.cipav.org.co/lrrd17/10/otch/17118.htm.

Sodjinou

E, Biaou G, Codjia J-C. 2002. Caractérisation du marché des escargots géants

africains (Achatines) dans les départements de l’Atlantique et du Littoral au

Sud-Bénin. Tropicultura 20(2), 83-88.

Zongo

D, Coulibaly M, Diambara O, Adjire E. 1990. Note sur l’élevage de l’escargot

géant africain Achatina achatina. Nature et Faune 6(2), 32-4.